Although people have lived in Alaska for at least 15,000 years, the first written accounts regarding the inhabitants are less than 300 years old. Much of what we know of the inhabitants who lived in Alaska thousands of years ago is based on archaeological evidence and is called prehistory. Other sources of information, particularly about the inhabitants of Alaska before Euroamericans arrived, are based on oral traditions of Alaska's Natives. The period for which these additional sources originated is called protohistory. Cultural information and physical evidence are studied to discover how people lived in the past. The prehistoric and protohistoric records form a base to which we add more recent oral traditions and written records that document Alaska's historical past.

Artifacts tell how Alaskans lived

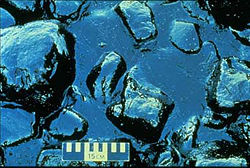

A chipped stone, a jade knife blade, a bit of copper can suggest how prehistoric Alaskans lived. Archaeologists look for these traces of the past. Sometimes they find places where earlier people stopped to build homes, catch salmon, or butcher whales. By examining such small details as the shape of a harpoon point or the etching on a pebble, these students of the past can describe how the hunters and fishers lived thousands of years ago. They can tell what other prehistoric people were related to early Alaskans. By studying the layers of soil, animal bones from old living places, and other information they can tell what the climate was like, what plants were cultivated, and what animals were hunted by prehistoric people.

Despite the archaeologists' skills, conclusions about Alaska's prehistory are incomplete. Many traces of early habitation have been found throughout Alaska, but only a few archaeological sites have been thoroughly studied. As more sites are closely examined, the story of Alaska's early people will become more detailed and accurate.

First hunters reach Alaska

The ancestors of Alaska's Indians, Eskimos, and Aleuts probably entered North America from Asia across a land bridge that was part of Beringia. Some might have come earlier over a smaller land bridge. Between 25,000 and 9,000 years ago, when sea level was much lower that it is today, land connected Alaska and Siberia. The bridge extended 1,000 miles north and south from the Gulf of Anadyr on Siberia's northeast coast to the western end of Umnak Island in the Aleutian Islands. Hundreds of years passed as people lived on the land bridge and moved across it from Asia to North America. Alaska was the first part of North America these people came to. Some of the people who crossed, particularly those who came more recently, settled permanently in Alaska.

Currently, some archaeologists think that there were three major migrations of people to Alaska. The migrations involved different groups of people and occurred thousands of years apart. The first migration occurred at least 15,000 years ago and possibly more than 25,000 years ago. These early immigrants are the ancestors of most Indian tribes in North and South America. The second group of immigrants are the ancestors of the Tlingits, Eyaks, and Athabaskans of Alaska and the Navaho and Apache people of the American Southwest. They moved from the northeastern forests of Siberia perhaps 9,000 to 14,000 years ago. The last group of immigrants moved about 6,000 to 10,000 years ago and some perhaps as recently as 4,000 years ago. They are the ancestors of the Eskimos and Aleuts. They came from the coast of northeast Siberia.

The oldest sites of proven human occupation in Alaska date back 11,000 years. One early site is Onion Portage, located on the Kobuk River in Northwest Alaska. Different groups of people lived at this site for thousands of years. The tools excavated from the most ancient soil layers are similar to those found in Siberia. They are the kind of tools that would have been used to cut meat, scrape hides, work wood, or make weapons.

On the Seward Peninsula, broken bones of bison and horses in Trail Creek Caves indicate humans were there as early as 11,000 years ago and possibly as early as 15,000 years ago. Early occupants probably hunted elk, horse, and caribou. They might also have worked and sewed skins.

In Interior Alaska archaeologists have found evidence at Healy Lake and Dry Creek, both north of the Alaska Range, that groups of people were there as early as 11,000 years ago. They were chiefly hunters and followed the caribou herds. In Southeast Alaska, Groundhog Bay in Icy Strait and Hidden Falls on Baranof Island near Sitka were probably campsites 8,000 years ago. The people gathered materials near these sites to make scraping and chopping tools. They fished and collected shellfish along the shore.

In the Aleutian Islands there is evidence that people lived together in a village there at least 8,500 years ago. The people at Anangula made pointed blades and scrapers, weights for fishing lines, and stone lamps and dishes. They made their living from the sea.

Territorial boundaries are established

By the mid-1700s between 60,000 and 80,000 people lived in Alaska. They included three separate groups of people: Indians, Aleuts, and Eskimos.

The Indians included the Tlingits and Haidas who lived in Southeast Alaska and the Athabaskans who lived in Interior Alaska. The Tlingits and Haidas numbered about 10,000 in the mid-1700s. The Alaskan Athabaskan population was about as large, but these people occupied an area about eight times larger than that occupied by the Tlingits and Haidas.

The Aleuts inhabited the Aleutian Islands and part of the Alaska Peninsula in Southwest Alaska. They numbered around 15,000 when the Euroamericans (people from Europe or European colonies in America) arrived.

The Eskimos lived along the Alaska coast from the Arctic Ocean to the northern boundary of Southeast Alaska near Yakutat. Eskimo territory included the tundra regions along the northern and western Alaska coast, Kodiak Island, part of the Alaska Peninsula, and Prince William Sound. The Eskimo population totaled around 30,000 by the mid-1700s.

Languages reflect changing cultures

All of the languages but two found i n Alaska today are related to two major language families. These two families are Eskimo-Aleut and Athabaskan-Eyak-Tlingit. The exceptions are Haida and Tsimshian. These are both languages of Native groups who lived in the Pacific Northwest. Eleven Athabaskan-Eyak-Tlingit languages are still spoken in Alaska. Eskimo-Aleut languages still spoken are Alutiia, Central Yupik, Siberian Yupik, Inupiaq, and Aleut. There were other languages and variations that have become lost over the millenniums.Cultures share common customs

By the 1700s when Euroamericans arrived in Alaska, the Tlingits, Haidas, Athabaskans, Eskimos, and Aleuts had defined territorial boundaries. They had a few common traits. They all were hunters and gatherers. They had no agriculture and only one domesticated animal, the dog. Each group had its own well established annual subsistence cycle based on the seasons and availability of animals and fish. Oceans, rivers, and lakes were their principal travelways and all of the groups had some kind of boat.

Shamans were important in each culture. This person, man or woman, looked after both the physical health and spiritual needs of the villagers. Shamans were the intermediaries between people and the spirit world.

A person's importance was often measured by his or her wealth. It might be represented by blankets, slaves, or other kinds of property. People acquired wealth not to keep, but to distribute to others. The rich gave away their wealth during Tlingit potlatches, Athabaskan festivals, Eskimo messenger feasts, and Aleut theatrical gatherings. These different ceremonies had the same purposes: to share wealth with the less fortunate and to obligate others to give gifts in return.

All Alaska Native groups expressed themselves artistically through earrings, face painting, labrets, tattooes, and decorated clothing. The people used whatever materials were at hand including wood, bone, stone, ivory, antler, feathers, porcupine quills, animal teeth, shells, and grasses. Dyes were made from berries, roots, and minerals.

Each group of Native Alaskans looked on itself as the center of the universe. Their names for themselves meant "the real people." Their explanations of the world included traditions of a supernatural being, usually Raven, as the creator of the world.

Native Alaskans also traded among themselves for things they needed. Trade fairs and trade trails connected interior people with coastal groups. In addition, some Euroamerican trade items, such as iron knives, passed from Native groups living outside Alaska to Native Alaskans before the Euroamericans themselves arrived.

http://www.akhistorycourse.org/articles/article.php?artID=148Alaska Native Heritage CenterWho We Are

The Athabascans traditionally lived in Interior Alaska, an expansive region that begins south of the Brooks Mountain Range and continues down to the Kenai Peninsula. There are eleven linguistic groups of Athabascans in Alaska. Athabascan people have traditionally lived along five major river ways: the Yukon, the Tanana, the Susitna, the Kuskokwim, and the Copper river drainages. Athabascans were highly nomadic, traveling in small groups to fish, hunt and trap.Today, Athabascans live throughout Alaska and the Lower 48, returning to their home territories to harvest traditional resources. The Athabascan people call themselves ‘Dena,’ or ‘the people.’ In traditional and contemporary practices Athabascans are taught respect for all living things. The most important part of Athabascan subsistence living is sharing. All hunters are part of a kin-based network in which they are expected to follow traditional customs for sharing in the community.

House Types and Settlements

The Athabascans traditionally lived in small groups of 20 to 40 people that moved systematically through the resource territories. Annual summer fish camps for the entire family and winter villages served as base camps. Depending on the season and regional resources, several traditional house types were used.

Tools and Technology

Traditional tools and technology reflect the resources of the regions. Traditional tools were made of stone, antlers, wood, and bone. Such tools were used to build houses, boats, snowshoes, clothing, and cooking utensils. Birch trees were used wherever they were found.

Social Organization

The Athabascans have matrilineal system in which children belong to the mother's clan, rather than to the father's clan, with the exception of the Holikachuk and the Deg Hit'an. Clan elders made decisions concerning marriage, leadership, and trading customs. Often the core of the traditional group was a woman and her brother, and their two families. In such a combination the brother and his sister's husband often became hunting partners for life. Sometimes these hunting partnerships started when a couple married.

Traditional Athabascan husbands were expected to live with the wife's family during the first year, when the new husband would work for the family and go hunting with his brothers-in-law. A central feature of traditional Athabascan life was (and still is for some) a system whereby the mother's brother takes social responsibility for training and socializing his sister's children so that the children grow up knowing their clan history and customs.

Clothing

Traditional clothing reflects the resources. For the most part, clothing was made of caribou and moose hide. Moose and caribou hide moccasins and boots were important parts of the wardrobe. Styles of moccasins vary depending on conditions. Both men and women are adept at sewing, although women traditionally did most of skin sewing.

Transportation

Canoes were made of birch bark, moose hide, and cottonwood. All Athabascans used sleds --with and without dogs to pull them – snowshoes and dogs as pack animals.

Trade

Trade was a principle activity of Athabascan men, who formed trading partnerships with men in other communities and cultures as part of an international system of diplomacy and exchange. Traditionally, partners from other tribes were also, at times, enemies, and travelling through enemy territory was dangerous.

Regalia

Traditional regalia varies from region to region. Regalia may include men’s beaded jackets, dentalium shell necklaces (traditionally worn by chiefs), men and women’s beaded tunics and women’s beaded dancing boots.

http://www.akhistorycourse.org/articles/article.php?artID=193